What biases affect your financial decisions? Now that Richard Thaler has won the Nobel Prize in economics for his groundbreaking research in the field of behavioral finance, perhaps we’ll all be more aware of our often-flawed decision making.

Dr. Thaler and other researchers in the field, such as Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, went against the current of mainstream economists who insisted that humans make calculated rational decisions, and that the markets are efficient. They looked at economics from a psychological perspective, which is often more difficult to measure. As fee-only financial advisors, we define this field of behavioral finance as the study of not-so-rational investment decisions.

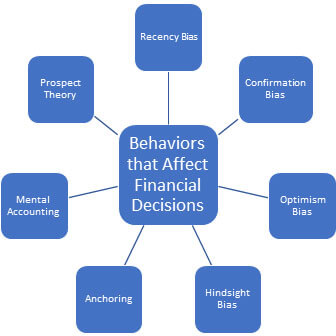

Dr. Thaler joked that he’s “going to try to spend his prize money as irrationally as possible.” But all jokes aside, there are dozens of reasons and underlying biases that cause people to behave irrationally, often against their best interests. Just knowing some them may help you avoid mistakes in the future and possibly give you a financial edge. Here are seven behavioral biases, some of which were identified and studied by Richard Thaler and others in this field.

1. Recency Bias

In our practice as financial advisors, we note that this one causes the most financial damage. Remember the fearful people in early 2009 thinking the Dow at 8,000 would continue all the way down to 2,000? Perhaps you were one of them. Recency bias means that we extrapolate the current trend well into the future. It causes people to buy near the top and to sell near the bottom, thinking that the trend will continue. Closely related to recency bias is Availability Bias in which people tend to give more credence to current events and new information than to the expense of the majority of the facts and the big picture.

Antidote

Stop and remind yourself that no trend continues indefinitely. Look at investment fundamentals—are they reasonable and sustainable? Try to put news in perspective and think long-term.

2. Confirmation Bias

We like to think that we carefully gather and evaluate facts and data before coming to a conclusion. But we don’t, for the most part. We find facts to fit our pre-conceived conclusions. Any sales training 101 class emphasizes that people buy emotionally, then justify it with facts after the purchase. This also happens with our political views.

Antidote

Seek out opinions and resources that don’t support your opinion. On the financial side engage the services of a professional investment manager with a rigorous analytical process and robust information sources.

3. Overconfidence or Optimism Bias

We like to call this the Lake Woebegone Bias (“where all the women are strong, the men are all good-looking, and all the children are above average”). We tend to think of ourselves and our decision-making ability as above average. Yet, we are only correct about 80% of the time when we are “99% sure.” 1 Studies show that 80% of drivers say that their driving skills are above average. 2 We suspect that none of them drive I-5 when we do. Confidence and optimism are good things when it comes to investing and financial planning. However, too much of a good thing can cloud your thinking.

Antidote

Ask yourself what can go wrong and realize that you are only one trade from a humbling wake-up call.

4. Hindsight Bias

Have you wondered why so many people now say that the events leading up to the creation of the Internet, the 2000 tech bubble, 9-11, or the 2008 market collapse were so obvious? They have hindsight bias, which stems from the innate need to find order in the world by creating explanations that allow us to believe that events are predictable. While it is helpful to learn why things happened, finding erroneous links between the cause and effect of an event may result in incorrect oversimplifications. Worse yet, if you forget how you came to those conclusions, you can develop a sense of overconfidence that you knew what others didn’t and that you know what others don’t.

Antidote

Try a little humility by reminding yourself that if all the experts didn’t see something coming, you probably didn’t either; otherwise, you would have acted upon your information. Be the first to admit that you don’t have all the relevant facts when making a decision.

5. Anchoring

This is the inclination to hold on to a viewpoint and apply it as a reference point for making future decisions. A shirt marked by a retailer with an original price of $100 seems like a bargain when it is 30% off, but was it really worth $100 to begin with? Maybe it’s really worth $50 or $60. Likewise, we do this with real estate and stock prices. Just because a stock was once $100 doesn’t mean that it is worth $100 at today’s fundamentals and earnings prospects. Many people today have anchored on to the Great Recession and the market downturn from 2007-2009. As a result they are still waiting for the next shoe to drop, thereby missing out on the recovery. Or, they hold onto an unprofitable asset waiting for it to “get back to even” because they think that is what it is worth.

Antidote

Try to find valid reasons for the anchor, and be open to new information if it contradicts your thinking.

6. Mental Accounting

Do you have separate pots of money for different goals? Or do you treat “found money” differently from earned money? If so, you are using mental accounting. It’s not necessarily a bad thing when you invest more conservatively for your 16-year old’s 529 college savings plan and more aggressively in your IRA which you won’t need for another 15 years. It’s quite another when you use different criteria for holding on to a losing investment and another set of rules for everything else. It’s also not a good thing when you sock away money for a new car into a low-interest savings account or spend your tax refund on a vacation when you have high-interest credit card debts.

Antidote

As financial advisors, we encourage our clients to recognize that money is fungible; regardless of its origins or intended use, all money is the same. Only your time horizon for each goal or an account’s tax characteristics are different

1 Daniel Kahneman & Dan Lovallo, “Timid Choices and Bold Forecasts: A cognitive Perspective on Risk Taking,” Management Science, Vol.39, No. 1, Jan 1993.

2 McCormic, Walkey, Green, “Comparative Perceptions of Driver Ability—a Confirmation and Expansion,” Pub Med.gov, 1986.

7. Prospect Theory

This area of behavioral finance covers a wide range of behaviors. At its core, prospect theory contends that people value gains and losses differently. Numerous studies have shown that the joy of a $100 gain on a $100 investment is offset by the pain of a $50 loss on it after it hit $200. Prospect theory also helps explain why people hold on to losing stocks for too long and sell winning stocks too soon. To sell a loser too soon is to come face-to-face with a loss.

Antidote

Before making an investment, ask yourself how you would feel and what you would do if your investment fell 25% or more. With your losing investments, ask if you would purchase that same investment today with what you know now. The odds are that you wouldn’t, so why hang on to it?

We are all human, so for most of us, money decisions are not always rational. If there is any common theme to the antidotes above it is to recognize the behavioral finance forces at work, gather information, ask questions of yourself, and think things through. As fee-only financial advisors, we can help you do this.